Systolic_blood_pressure

I take my blood pressure always in the evening, after I get to bed with my Withing blood pressure monitor, while sitting in the bed. I do this semi-regularly, about once a week, but I had periods where I did it nearly daily, but also longer gaps, for example due to holidays. In this post I will only look at systolic blood pressure, as it is usually the more informative biomarker than diastolic blood pressure.

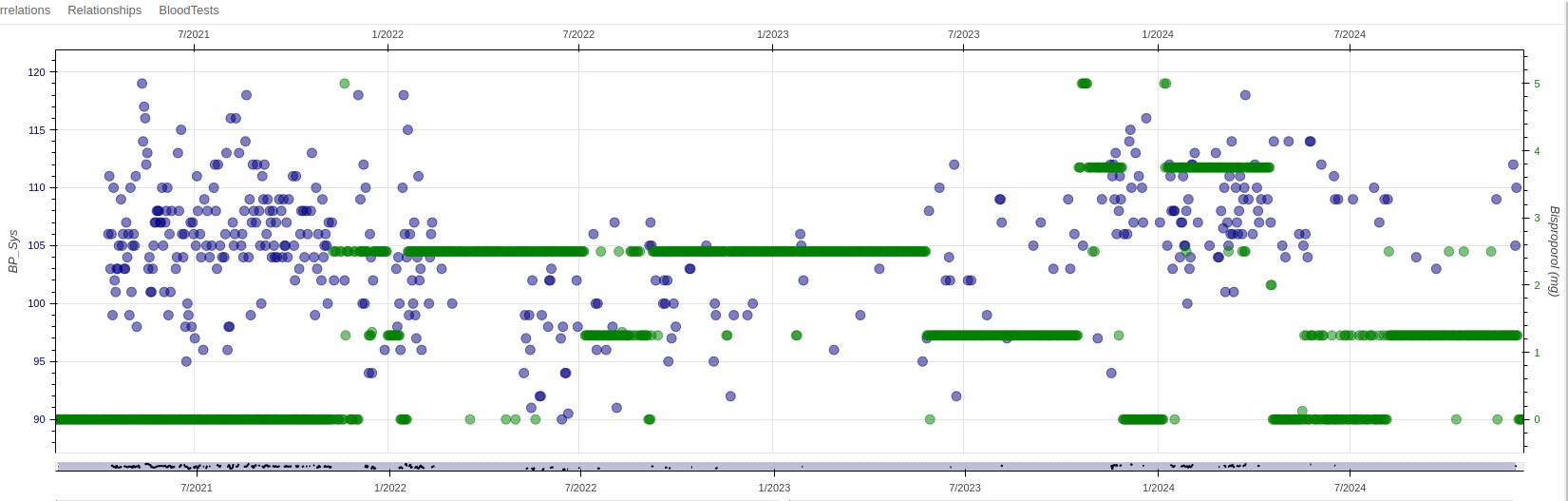

Bisoprolol

The only medication I take long term (it will be now about 4 years) is a beta-blocker, specifically Bisoprolol. I am a somewhat neurotic personality, and I believe I was my whole life running on slightly higher gear of sympathetic system than average person. Its in my family. About 4 years ago I started to occasionally get feeling of palpitations and noticed occasional ectopic beats. I believe that combining with my predisposition, it was triggered by a period when I was starting to experiment with high insensitivity interval training (HIIT) coinciding with particularly stressful period at work. In any case, I consulted doctor who put me on preventive dose of beta-blockers. All subsequent tests of cardiovascular system came out negative, but since the beta-blockers seem to alleviate my symptoms which I find rather uncomfortable even if they are harmless, my doctors were happy to let me take the minimal prescribed dose of Bisoprolol. In fact most of the time these days, I only take half of that minimally prescribed dose, yet I clearly feel its positive impact so I keep using it.

In any case, one of the main and exceedingly well documented impacts of beta-blockers is reduction of blood pressure, even if typically rather small, and so it would make sense to investigate it first. Indeed I do find a mild but robust correlation between systolic blood pressure and Bisoprolol dosage (R=-0.14;p=0.003;N=397):

Interestingly, as you will see, despite being dedicated medication, as you will see there are other interventions that seem to have greater impact on my blood pressure than Bisoprolol.

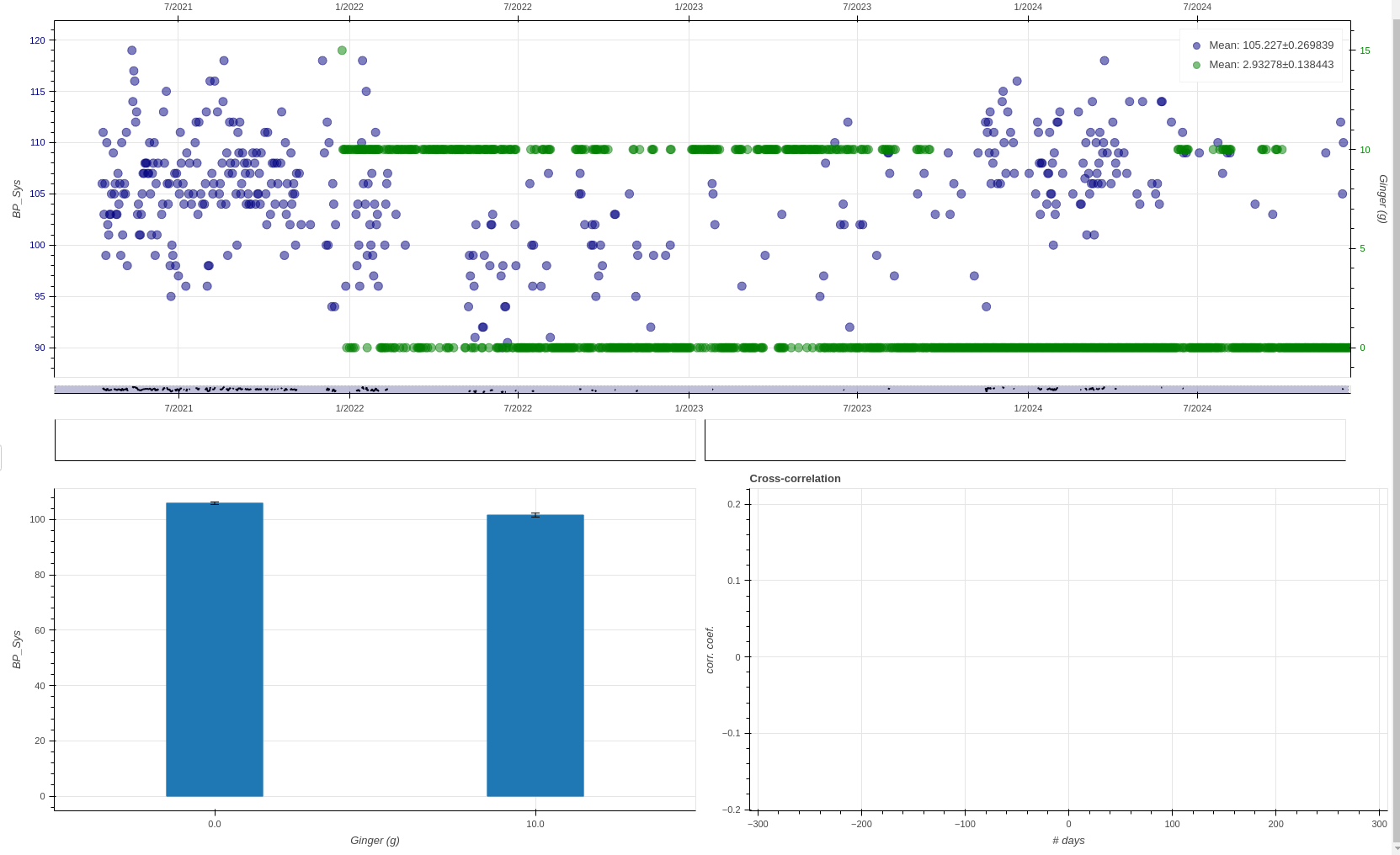

Ginger

The strongest dietary correlate for blood pressure I get is fresh Ginger that I add to my smoothies (R=-0.34;p<10^-7;N=214):

As you can can see, I was consuming ginger during a one long 2 year period, which is particularly well aligned with the dip in my blood pressure. Lately, my blood pressure went slightly up, but unfortunately I wasn’t taking BP readings very diligently lately, neither was I consuming fresh ginger often so I cannot exclude that there was only an accidental alignment between that period of ginger consumption and lower blood pressure. But also prior studies show that ginger can have positive effect on blood pressure so that would corroborate my findings [1].

I am planning to reintroduce ginger into my smoothies, and take BP readings more often, because I am rather intrigued by this surprisingly strong effect.

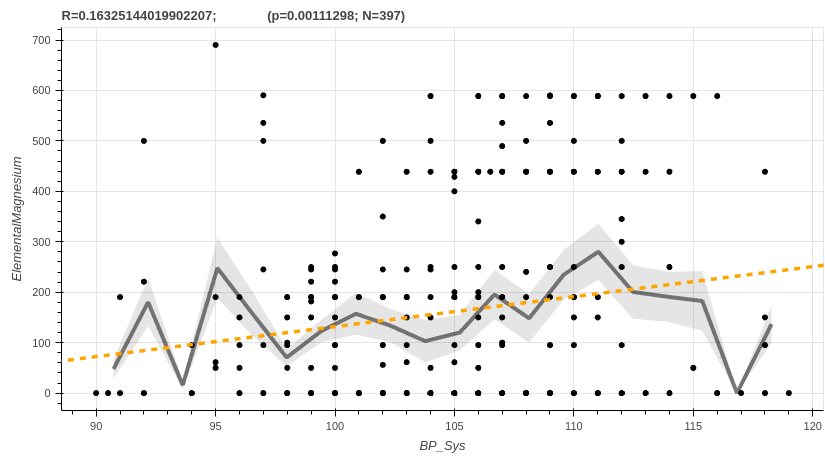

Magnesium

I was supplementing magnesium in multiple forms in the last few years, and the total intake of elemental magnesium seems to be positively associated with my systolic blood pressure (R=0.16;p=0.001;N=397).

Over the years, I supplemented multiple forms and the one that seems to be most strongly associated is magnesium malate, but I am not confident that the specific form matters. This observation is rather surprising as it has been shown in multiple clinical studies that magnesium supplementation should have the opposite effect. It is true that I have been supplementing relatively higher doses (about 180mg of elemental magnesium per day), but this seems to be an unlikely explanation.

Calcium AKG

Another supplement that is positively associated with systolic blood pressure is the Calcium AKG (R=0.24;p=0.005;N=126).

Radicchio

I added radicchio into my diet about two years ago, mainly due to it being one of the best natural sources of luteloin [2], which in turn is known to inhibit the CD38 enzyme, which has number of positive downstream effects, including on NAD metabolism. I always use this variety, and add it to my salads:

I tend to eat salad about 4-7 times a week, but often it is difficult to get hold of radicchio in summer and autumn month where I live, so there is some seasonality to when I eat it.

In any case, quite surprisingly, radicchio has association with my systolic blood pressure. This is surprising given that it is all over internet touted for its supposed blood pressure reducing qualities, but the only study that the websites I checked were referring to (if anything at all) is this [3]. This study however doesn’t actually talk about radicchio, but roasted chicory root, which is only related to radicchio in that radicchio is a particular variety of a cultivated chicory plant, but we eat the leafs not root, and of course radicchio may have substantially different biochemical composition to the wild chicory plant.

With all this in mind, my blood pressure is in optimal range irrespective of the radicchio consumption, so I will be keeping it as a part of my diet for its other properties (see luteloin) for the time being, but I will keep this in mind for future in case blood pressure would become an issue with advancing age.

[1] Hasani H, Arab A, Hadi A, Pourmasoumi M, Ghavami A, Miraghajani M. Does ginger supplementation lower blood pressure? A systematic review and meta-analysis of clinical trials. Phytother Res. 2019 Jun;33(6):1639-1647. doi: 10.1002/ptr.6362. Epub 2019 Apr 11. PMID: 30972845.

[2] Hostetler GL, Ralston RA, Schwartz SJ. Flavones: Food Sources, Bioavailability, Metabolism, and Bioactivity. Adv Nutr. 2017 May 15;8(3):423-435. doi: 10.3945/an.116.012948.

[3] Nishimura M, Ohkawara T, Kanayama T, Kitagawa K, Nishimura H, Nishihira J. Effects of the extract from roasted chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) root containing inulin-type fructans on blood glucose, lipid metabolism, and fecal properties. J Tradit Complement Med. 2015 Jan 20;5(3):161-7.

Leave a comment

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *